If you spend enough time listening to House Republicans Chip Roy, Matt Gaetz, and Lauren Boebert you will soon hear about the Uniparty. In right-wing dogma, the concept of the Uniparty has existed for about a decade, and has become de facto far-right Republican doctrine.

That is, a shadow party composed of both moderate Republicans and Democrats, is the backbone of Washington. And according to them, it is up to patriotic Americans to disable and destroy it in any way possible. In doing so, the “swamp” will be drained, and Americans will experience true freedom and liberty.

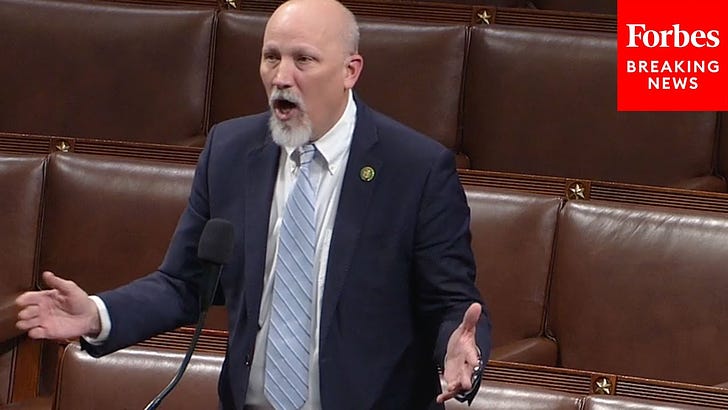

Today in a speech on the House floor, Chip Roy (R-Texas) mentioned the Uniparty:

We used to have a lot of back-and-forth between Democrats and Republicans…we used to accuse them of being tax-and-spend Democrats…Then something changed along the way, and we stopped debating tax policy…and now everybody in this Congress, for the most part, are spend-and-spend members of Congress…spend-and-spend members of a Uniparty.

The concept is not as outlandish as it sounds. One academic theory put forth by historian Michael F. Holt, says the concept of a Uniparty was a primary cause of the 1850s political crisis that led to civil war. Then, the two major political parties of the time - the Whigs and the Democrats - effectively became a Uniparty.

What were the signs of a Uniparty in the early 1850s? Then, it appeared to most observers that traditional political issues no longer existed, because they had all been resolved, and therefore both parties had similar views. Thus, there was no longer conflict between the parties, and no reason to vote for one party over another. Without distinctive political differences between the two parties, the Second Party System then imploded into a political muddle.

Americans no longer felt they had their one and only way of changing the system - through their vote. By the late 1850s, the political system devolved into blatant sectionalism as there were no other issues to fight about. The system fanned the flames of sectional conflict until the start of war in 1861.

This feeling of the death of republicanism was felt most strongly in the Southern states, where the Whig party died first - the early 1850s in the Deep South, whereas the Upper South and Northern states had a functioning Whig party until the mid 1850s. Thus, former Whigs in the South had a longer period of time with no effective way of exercising their political will to affect change in local, state, and Federal government - and then most Southern states were effectively one-party states (Democratic).

By contrast, in northern states, a series of new political parties formed to replace the Whigs. The anti-Catholic and nativist Know Nothings, later known as the American Party, is one example. They were eventually absorbed by the new Republican Party by the late 1850s.

In both sections, but particularly in the South, these feelings of political drift led Americans to believe that republicanism and democracy itself were dying. This dread caused Americans, North and South, to radicalize in order to “preserve republicanism and return power to the people.” (Holt 5) This same feeling would also fuel the euphoric delirium of Southern secession in the winter of 1861, when the election of Abraham Lincoln as the first Republican president seemed to confirm the South’s worst fears of their political futures.

Holt, Michael F. The Political Crisis of the 1850s. New York, Wiley, 1978.