You may be wondering why I am discussing George Washington to the extent that I have, when Lincoln is ostensibly the subject of this Substack.

It is not an understatement to say that Abraham Lincoln considered George Washington to be one of his greatest political influences and role models. He read Washington biographies incessantly in his youth, and even became a surveyor, just as Washington had, during his young adult years. Lincoln probably would never have become a politician without Washington’s influence on his life.

So in order to fully understand Lincoln, a solid understanding of Washington must come first.

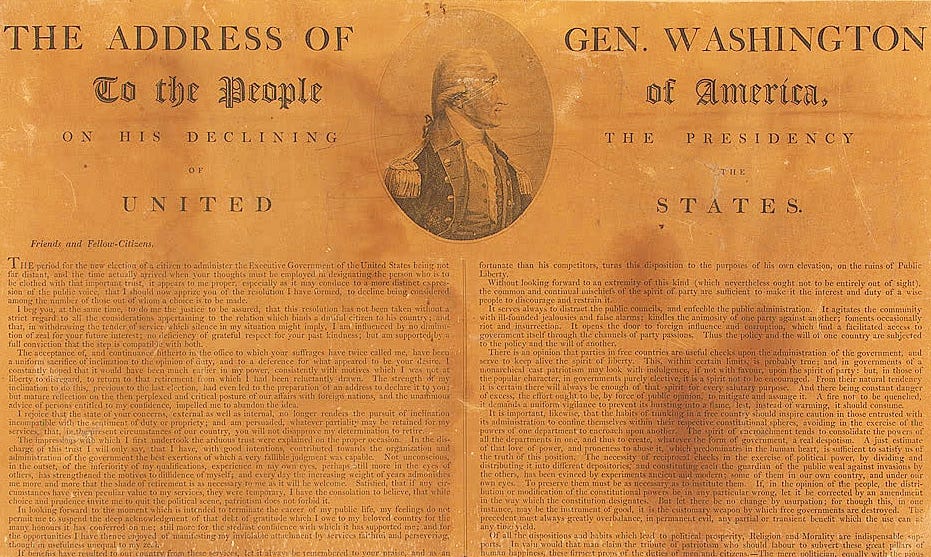

Today we will analyze verbatim quotations from Washington’s Farewell Address published on 19 September 1796.

Washington’s statements are in quotations, and my comments are italicized. Bolded statements are what I consider to be crucial to understand in terms of Washington’s original vision for the United States.

“The nation which indulges towards another an habitual hatred or an habitual fondness is in some degree a slave. It is a slave to its animosity or to its affection, either of which is sufficient to lead it astray from its duty and its interest. Antipathy in one nation against another disposes each more readily to offer insult and injury, to lay hold of slight causes of umbrage, and to be haughty and intractable when accidental or trifling occasions of dispute occur. Hence frequent collisions, obstinate, envenomed, and bloody contests. The nation, prompted by ill will and resentment, sometimes impels to war the government, contrary to the best calculations of policy. The government sometimes participates in the national propensity and adopts through passion what reason would reject; at other times, it makes the animosity of the nation subservient to projects of hostility instigated by pride, ambition and other sinister and pernicious motives. The peace often, sometimes perhaps the liberty, of nations has been the victim.”

This was the policy of neutrality that was official United States policy until the end of the 19th century. Washington warns that foreign alliances would lead to foreign entanglements that are ultimately not in the country’s interests. Emotions and passion would tempt us to intervene, but it would be a mistake and inevitably we would lose our liberty and be less free, since we now are required to answer to at least one, and likely more, foreign powers.

“So likewise, a passionate attachment of one nation for another produces a variety of evils. Sympathy for the favorite nation, facilitating the illusion of an imaginary common interest in cases where no real common interest exists, and infusing into one the enmities of the other, betrays the former into a participation in the quarrels and wars of the latter without adequate inducement or justification. It leads also to concessions to the favorite nation of privileges denied to others, which is apt doubly to injure the nation making the concessions—by unnecessarily parting with what ought to have been retained—and by exciting jealousy, ill will, and a disposition to retaliate in the parties from whom equal privileges are withheld. And it gives to ambitious, corrupted, or deluded citizens (who devote themselves to the favorite nation) facility to betray or sacrifice the interests of their own country without odium, sometimes even with popularity; gilding with the appearances of a virtuous sense of obligation a commendable deference for public opinion, or a laudable zeal for public good, the base or foolish compliances of ambition, corruption, or infatuation.”

This is applicable to Ukraine today. Washington tells us in detail how our current involvement with Ukraine can backfire for the U.S., and even Ukraine itself. Interestingly, Washington states that by assisting the “favorite nation”, we could actually be harming them by encouraging them into a fight that they would not pursue otherwise, and provoke jealousy in third parties that are not receiving aid. Not only that, but it would lengthen the conflict and heighten the severity. In addition, factions would form in the donating nation who can take advantage of the issue for for their own unscrupulous reasons.

In short, Washington was not willing to risk domestic disharmony and strife for the needs of a foreign power. There was too much to lose and not enough to gain, and the mass unhappiness it causes would be one of the few things that would bring the American experiment to a premature end. In the early years of the nation this was even more important. Perhaps his views would have moderated as the nation became more established.

It must be said that Washington lived in a different time when isolationism was much more practical. But we need to be mindful of Washington’s vision for the future in regards to foreign wars and alliances. If our circumstances in the 21st Century allow a safe return to Washington’s vision, then it should be considered, as it is the true nature of what the United States was meant to be.

Would Washington have continued a policy of neutrality and non-intervention through the 20th century and today? If only we could know his thoughts on the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

In addition, would true isolation be possible in the age of instant global communication and pocket video cameras? It was relatively easy to ignore a war thousands of miles away when you weren’t constantly bombarded with eyewitness details and shocking videos of the carnage on social media. I don’t think I, or even Washington himself, would want to share a country with someone who didn’t feel that they wanted to help such a nation on a visceral level. But Washington stressed that logic and thoughts must dictate policy, not short-term emotional responses. Another complicating factor in today’s world would be the mass guilt and unhappiness if we did not assist in some concrete way. Washington warned against the emotional factor, but perhaps that was one aspect of human nature he underestimated?

“As avenues to foreign influence in innumerable ways, such attachments are particularly alarming to the truly enlightened and independent patriot. How many opportunities do they afford to tamper with domestic factions, to practice the arts of seduction, to mislead public opinion, to influence or awe the public councils! Such an attachment of a small or weak towards a great and powerful nation dooms the former to be the satellite of the latter.”

This is reminiscent of our recent experiences in Afghanistan. Washington states again that foreign involvement will eventually come back “home to roost.” What Washington called “designing men” would tamper with domestic factions; mislead and influence the public. The smaller nation would become our “satellite,” and then permanent involvement would result.

“Against the insidious wiles of foreign influence (I conjure you to believe me, fellow citizens) the jealousy of a free people ought to be constantly awake, since history and experience prove that foreign influence is one of the most baneful foes of republican government. But that jealousy to be useful must be impartial; else it becomes the instrument of the very influence to be avoided, instead of a defense against it. Excessive partiality for one foreign nation and excessive dislike of another cause those whom they actuate to see danger only on one side, and serve to veil and even second the arts of influence on the other. Real patriots, who may resist the intrigues of the favorite, are liable to become suspected and odious, while its tools and dupes usurp the applause and confidence of the people to surrender their interests.”

The great rule of conduct for us in regard to foreign nations is, in extending our commercial relations, to have with them as little political connection as possible. So far as we have already formed engagements, let them be fulfilled with perfect good faith. Here let us stop.

Europe has a set of primary interests, which to us have none, or a very remote relation. Hence she must be engaged in frequent controversies, the causes of which are essentially foreign to our concerns. Hence therefore it must be unwise in us to implicate ourselves, by artificial ties, in the ordinary vicissitudes of her politics or the ordinary combinations and collisions of her friendships or enmities.

Our detached and distant situation invites and enables us to pursue a different course. If we remain one people under an efficient government, the period is not far off when we may defy material injury from external annoyance; when we may take such an attitude as will cause the neutrality we may at any time resolve upon to be scrupulously respected; when belligerent nations, under the impossibility of making acquisitions upon us, will not lightly hazard the giving us provocation; when we may choose peace or war, as our interest, guided by justice, shall counsel.

Why forgo the advantages of so peculiar a situation? Why quit our own to stand upon foreign ground? Why, by interweaving our destiny with that of any part of Europe, entangle our peace and prosperity in the toils of European ambition, rivalship, interest, humor, or caprice?

It is our true policy to steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world—so far, I mean, as we are now at liberty to do it—for let me not be understood as capable of patronizing infidelity to existing engagements (I hold the maxim no less applicable to public than to private affairs, that honesty is always the best policy)—I repeat it therefore, let those engagements be observed in their genuine sense. But in my opinion it is unnecessary and would be unwise to extend them.

Taking care always to keep ourselves, by suitable establishments, on a respectably defensive posture, we may safely trust to temporary alliances for extraordinary emergencies.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Washington%27s_Farewell_Address